From Wired a detailed report on the Version Variation Visualization Project and their first prototype Translation Array.

From Wired a detailed report on the Version Variation Visualization Project and their first prototype Translation Array.

A team at Swansea University has developed an online tool that allows researchers to compare multiple translations of Shakespeare at the same time to see how much they vary.

The platform can be used for any text, but has been demonstrated with Act 1, Scene 3 of Shakespeare’s Othello, where the eponymous hero gives a persuasive speech about his courtship of Desdemona to her disapproving father Brabantio and others. Users can compare the original base English text (Michael Neill’s OUP edition) with any one of 37 different German editions, dating from 1766 to 2010 — something that the team calls a “translation array”.

The most intriguing tool is the “Eddy value” tool which allows you to select individual lines from the scene and compare them to the translations from the 37 different German editions (the aim is to add in further languages and additional scenes, but the project needs more funds to do this). Based on analysis of all of the translations, each of the individual line translations has been awarded a numerical value. The higher the Eddy value, the more distinctive the translation, i.e. the more it stands out from the crowd. The value is calculated using word frequencies in the whole set of translations.

Linguist Tom Cheesman, who heads up the project at Swansea University explains: “If you say ‘deviation from a norm’, it is misleading, conceptually and statistically. Translation doesn’t work like that: people think there’s a ‘right version’ and then various kinds of mistake. No: it’s about differing interpretations, not about right and wrong.”

Each of the German translations is then run back through Google Translate so readers can see a direct comparison of the differences in the words used.

The level of agreement there is on certain lines is then reflected in the highlighting of the English text — the darker the blue highlighting, the more variability there is in the translations of that line. For example, Brabantio’s words “Here is the man, the Moor” has been variously translated, but most German editions use the words “Hier ist der Mann, der Mohr”, although you can see that the 1992 Motschach edition uses the sentence: “Da steht der Mann: der schwarze Teufel”, where “schwarze Teufel” means “black devil”. In this way, readers can begin to understand the rich variation of interpretation.

Cheesman told Wired.co.uk: “The aim is to document the history of the play and its translations. They are implicitly aligned with each other. Digital technology is great for exploring their connections and deviations.

“Do men translate differently from women? Do East German translations of Shakespeare differ from West German? How has the depiction of Othello as a black man changed through history, from the time of slavery, through the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm, to the Nazi dictatorship, and up to the present time of ‘political correctness’?”

In the “Parallel” view, readers can see line-by-line comparisons of the translation, seeing how the form of the lines compares to the original text.

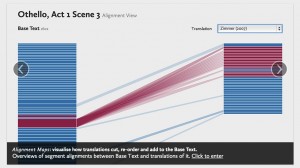

The “Alignment” tool provides a visual representation of the English version and then any one of 37 translations, linking corresponding lines to show how the translation affects the form of the text. This is particularly useful when comparing the original text to Felsenstein’s translation of the Italian libretto based on Shakespeare’s play used in Verdi’s opera. The view allows you to see how only small sections of the original play were repurposed and reordered.

The project was born out of an original idea of Cheesman to compare just two lines of Othello, spoken by the Duke of Venice: “If virtue no delighted beauty lack/ Your son-in-law is far more fair than black.”

He set up a website — called Delighted Beauty — where people could submit the translations of those lines from dozens of different countries and publishers. Users can then scroll through the different versions, be they in Bulgarian, Greek, Korean or even Old Church Slavonic. However, the data was not presented in the most interactive or intuitive way.

The new platform, was built using funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, aims to provide simple navigation through different texts and visualisations of structural differences among translations.

Cheesman worked with software architect Kevin Flanagan, design studio Studio Nand, ABBYY and Computer Scientist Zhao Geng. They are now looking for more funding so that they can build on the number of texts available and the analytical tools. He hopes to add the Merchant of Venice court room scene (Act 4, Scene 1) to the platform next.

To try the tool for yourself, visit this link. You can login using the details that are supplied on the login page, then click on Corpara along the top menu (Cheesman acknowledges that the navigation could do with some work). In Corpara, select Othello and then choose from the different views found in the top right.

Very intresting. If this works for versions so different from each other as translations, how well it might work for medieval manuscripts carrying the ‘same’ text in a textual tradition!